July 21, 2025

Kathmandu, Nepal

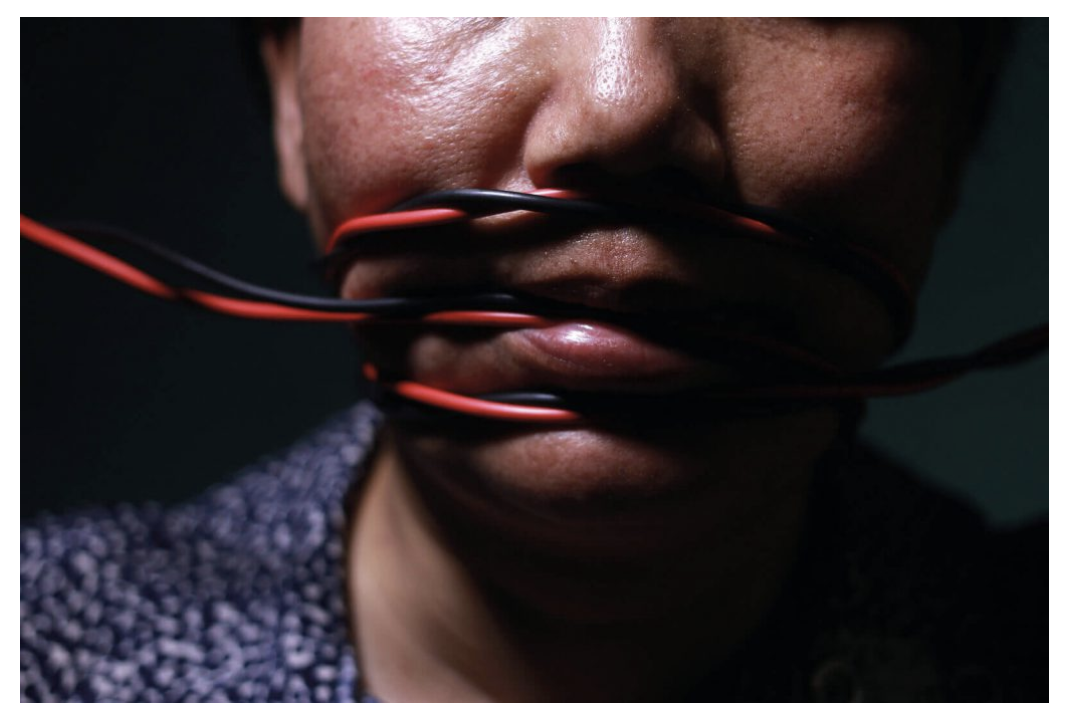

Palsang, one of the countless survivors of wartime torture in Nepal, bears lasting psychological scars inflicted by the Nepal Army. Bound by trauma and haunted by nightmares, her story speaks to the enduring pain of a silenced generation.

Nepal’s civil war began in February 1996 when the Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist) launched an armed insurgency to dismantle the monarchy and establish a people’s republic. Lasting more than a decade and claiming over 17,000 lives, the conflict found significant support among marginalized communities, particularly subaltern women (from lower castes and oppressed backgrounds).

The Maoists’ promise to end caste and gender hierarchies resonated in a society shaped by Hindu patriarchy, where women were confined to domestic roles and denied access to education, property, and public services. For many of these women, joining the movement as combatants, medics, and leaders provided a sense of agency, dignity, and political relevance--- something they had never experienced before.

However, the promises of equality and justice were not fully realized. Many of these same women endured extreme hardship during the war, including sexual violence. Both state and non-state actors strategically employed rape to intimidate, punish, and exert control. The survivors, often young and from marginalized castes, were met with stigma, silence, and neglect.

Despite early commitments by the Maoist leadership to publicly punish rapists and elevate women to positions of power, the realities of conflict-related sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV) were largely ignored in post-conflict mechanisms. Many women were excluded from reparation efforts and denied formal recognition. In the end, many who had taken up arms in pursuit of liberation became victims of the very violence they had set out to resist.

Sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV) is a deeply entrenched yet often overlooked aspect of armed conflict. While wars are typically seen as struggles for territory or political control, they also create conditions or intensify existing of gender inequalities. Women and girls—especially from marginalized communities—are not merely collateral damage; they are frequently targeted with intent, using sexual violence to dominate, humiliate, and fracture communities.

Female Maoist fighters of the 13th Battalion, including Onsari Gharti Magar (Usha), who later became House Speaker, pose with rifles during the insurgency.

According to the United Nations, conflict-related sexual violence is not just an unfortunate byproduct of war spiraling out of control. Rather, it is often systematic and carried out under direct orders. In conflicts such as those in Rwanda, India, Pakistan, and the Democratic Republic of Congo, rape and sexual violence have been deliberately employed to destabilize entire communities and inflict long-term harm.

Nepal’s civil war followed this same disturbing pattern. As the Maoist insurgency escalated, so did the use of sexual violence by both state forces and rebel groups. Women and girls were subjected to systematic rape, harassment, and psychological torture. The situation was further worsened by the collapse of law and order during the conflict, allowing perpetrators to act without any fear of consequences. Victims and survivors alike were left to cope with the aftermath alone, often silenced by shame or threatened into submission.

Legal systems, already weakened by the war, failed to respond. In the years that followed, transitional justice efforts in Nepal have largely ignored the needs of SGBV survivors, pushing their stories to the margins.

The true cruelty of conflict-related SGBV lies in its enduring impact.

Survivors in post-conflict Nepal continue to face stigma, social rejection, and exclusion from legal or medical support. Many suffer from long-term physical and psychological trauma. Some are raising children born of rape, adding another layer of difficulty to their lives. Even though global frameworks like UN Security Council Resolution 1325 have called for justice and inclusion, most survivors in Nepal have yet to see meaningful change.

Armed conflicts do not affect all civilians equally. During the 10 years of Nepal’s civil war, pre-existing inequalities based on caste, gender, and class were not only exposed but also intensified. The Maoist movement’s promise of liberation and equality drew many women, particularly from marginalized communities, into the revolution.

Though the war offered many women a sense of purpose and agency for the first time, it did not shield them from violence. In fact, many became direct victims of sexual and gender-based violence, targeted by both state forces and rebel groups.

The consequences of this violence continue to shape the lives of survivors today. Activist and counselor Pooja Pant, who has worked closely with survivors of conflict-related sexual violence, describes the harm as not only physical and emotional but also systemic and long-lasting. "Most of the rapes during the war were committed by state forces against civilians," she explains. "And each woman has a different idea of what justice means."

For many survivors, justice remains out of reach. The stigma surrounding sexual violence is so pervasive that some women have never told anyone what happened, not even their families. Some long for legal recognition. Others do not even know who their perpetrators were. But almost all of them want acknowledgment. They want their pain to be seen and their dignity restored.

These survivors continue to live with the consequences. Many suffer from reproductive health complications but cannot afford treatment. Mental health care is almost entirely out of reach. "These women cannot work. They live with physical limitations and receive no support from the government," Pant says. "The government needs to see them. The government needs to care."

In Basantapur, trauma specialist Jamuna Shrestha works with Sajha Dhago, an organization focused on healing the deep emotional scars left by conflict. Her counseling work has brought her face-to-face with many women carrying unspoken trauma. One of them was Devi, a survivor whose story was later turned into a documentary by Subina Shrestha.

Shrestha met Devi at the height of the war. Devi was emotionally unstable, unable to express what she had endured, and often lost consciousness. Shrestha suspected sexual violence and arranged medical tests. Devi had been arrested, and since then, had not menstruated. When the pregnancy test came back negative, Shrestha saw a visible relief pass across her face.

After her treatment, Devi returned to the battlefield. Shrestha did not see her again for 20 years. But she never forgot about her. She often pictured Devi still fighting, surviving, and holding on.

Years later, Devi resurfaced. She had survived the war, married, had a child, and even entered politics. She ran for the parliament in Dolakha and won. However, her political life came with repeated death threats—threats that only ceased after she publicly forgave her perpetrators.

Still, her trauma did not fade. Two decades later, she was still grappling with nightmares, mood swings, and untreated PTSD.

Eventually, Devi sought out Shrestha's help. Their reunion, after so many years, was deeply emotional. During the filming of her documentary in 2021, Shrestha could see that Devi’s trauma had never fully left her. It surfaced in her expressions, her silences, and the way she carried herself. Shrestha also knew that Devi still trusted no one else. That trust brought them back into each other’s lives, and they began working together again.

Reflecting on her journey, Devi often spoke about the women who had no support systems at all. If she, with a supportive husband and family, continued to struggle so deeply, she wondered what life must be like for those who had been facing it alone.

An identification card issued by the People’s Liberation Army of Nepal (Janamukti Sena Nepal) during the Maoist insurgency, featuring a female commander and highlighting the participation of women in the armed struggle.

Unlike survivors of other wartime violence, women who experienced rape have received little or no compensation from the state. Many had no documentation of their trauma. Some gave birth to children conceived through rape and were later abandoned by their families. These children were left stateless for years until a legal reform allowed citizenship through the mother. Several of these children later died by suicide. Today, many survivors are married but have never disclosed their past to their husbands or in-laws.

Shrestha and Pant both believe the most urgent need is formal recognition and compensation. These women are not seeking charity—they are demanding justice, recognition, and dignity. Devi and her team are gathering evidence and testimonies across the country to present to the government in hopes of securing long-overdue reparations.

The team has also conducted health camps in five to six provinces. During these camps, several people were diagnosed with cancer. Jamuna believes these illnesses could be a part of the long-term consequences of war and trauma. The state, she says, must take responsibility.

Through Sajha Dhago, Shrestha now uses non-verbal therapy techniques to support survivors. She explains that traumatic memories often remain as vivid images in the brain. Through the Story Cloth project, women are encouraged to express these memories using cloth, thread, and needle. In this quiet act of stitching, survivors begin the process of healing. They take something internal and invisible and give it form, something they can see, hold, and eventually, release.

Meanwhile, digital platforms like memorytruthjustice.com continue to preserve these testimonies. Survivors are telling their stories not for sympathy, but to be included in Nepal’s collective memory. They want space in the narrative of war and peace. They want the truth to be acknowledged.

The war may be over. But for many of these women, the fight to be seen—and heard—is still ongoing.

By sharing valuable information and sparking inspiration, we aim to foster growth, innovation and brighter opportunities for future generations.

Contact us